#22--Published October 1970

GOLDEN CITIES, FAR

Lin Carter, ed.

Cover art by Ralph Iwamoto and Kathleen Zimmerman

Like the previous world tale collection in this series (see #7: "Dragons, Elves and Heroes"), Lin Carter has put together a marvelous volume that can not only be enjoyed in its own right, but should lead the reader to many other sources as well. Whetting the appetite for more is hardy praise for such a book. This particular volume has been in my collection since my teens, and it always was graced by my favourite title of the entire series. However, until now I had never read it!! In addition to an introductory essay for the collection, Carter presents each of the thirteen tales with a proper introduction. I would also like to say a word or two about each of the stories, by way of a review.

How Nefer-Ka-Ptah Found the Book of Thoth, from an Egyptian papyri and retold by Brian Brown, tells the tale of a king's son, an avid reader, and his pursuit of the ultimate book. How he achieves this marvelous feat, and at what cost, makes for a short but sweet beginning to this volume. If you like this opening story, as I did, then you will likely enjoy the rest of the book.

The Descent of Ishtar to the Netherworld is a short poem (translated by Carter himself), and is a bit pedestrian by comparison. However, it has all the ingredients of a great fantasy epic, proving beyond a doubt that authors from any age are capable of unleashing their imagination in ways that can still be appreciated by readers distant in time and location.

Prince Ahmed and the Fairy Paribanou is a tale from the Arabian Nights, though not one published by Burton. Though loosely connected, it is in two distinct parts, and they each make good separate tales. The second one is the better of the two, and really captures the spirit of these rich tales nicely. I have not read any of the Arabian Nights tales now in many years, but will soon undertake some of them again. A loyal son, distrusted and abused by his father the Sultan, goes well out of his way to make his unique way in the world. This is one of the best stories in the present volume.

Of course the Thousand and One Nights stories became hugely popular, ushering in an age of Orientalism in Europe that was to last over a century. James Ridley wrote a volume of original tales entitled "The Persian Tales of the Genii," and Carter has selected The Merchant Abudah's Adventure with the Ivory Box for this volume. Nearly as rich and captivating as the original Arabian Nights tale above, we follow Abudah's various bizarre adventures as he searches for the talisman of Oromanes, egged on by a tiny old hag that pops out of a tiny ivory box every night to torment him. We follow our hero/merchant through four significant adventures, each one stranger and more fantastic than the previous one. I enjoyed all of it right up until the final paragraph...

Wars of the Giants of Albion is from the Welsh Historia Regum Britanniae by Geoffrey of Monmouth. The tale told here describes how Britain came to be settled and ruled. Though a lot of the material I have reviewed so far might sound a tad on the dry side, it is anything but. Almost all of the stories, and this one in particular, are easy to read by the lover of fantasy writing. If you are interested in writing fantasy, you will also learn a lot about storytelling from these wonderfully imagined tales!

Forty Singing Seamen is a ballad on an old legend by Alfred Noyes, telling a fantastic tale that could be real or could be imagined.

We move next into Carolingian literature. Huon of Bordeaux is a medieval French romance translated by Sir John Bourchier and retold by Robert Steele. If you like Arthurian romance or other tales of chivalry, this story will please greatly. The Shadowy Lord of Mommur is the title of this excerpt. I have not talked much about the humour in many of the stories. This tale is a good example of that aspect, which many of the others also share. The hero is given a cup and a horn by King Oberon, and their magic is interwoven throughout the story. The cup will always be filled with wine for all who are thirsty. The horn, if blown, will immediately summon King Oberon and his army to aid the hero. He is not to use it unless circumstances are exceedingly dire, upon pain of death and much suffering. Of course our hero must try it out to see if it really works...

Olivier's Brag is a modern treatment of the Carolingian theme by Anatole France. This one features Charlemagne himself, along with his twelve cohorts, as they are guests of a certain King. Later that night, housed in their quarters, they take turns bragging (all in fun) about what exploits they might achieve next day, many of which are very hostile and unflattering to their host, including destroying his castle and making off with his daughter. The King overhears their brags, and next day forces each of them to fulfill his boast or die. Very short and very amusing!

The White Bull is the second tale by Voltaire to make it into this series (the other is in "Dragons, Elves and Heroes"), and is a highlight of the collection. The tale concerns a princess whose lover has been turned into a great white bull, and her efforts to restore him to his former self. Told in eleven short chapters, this is a "do not miss" part of the volume. Highly recommended.

The Yellow Dwarf is a French fairy tale. Fairy tales these days are aimed mostly at children, but that was not their original intended audience. Bellissima is the only surviving daughter of the Queen, and is sought after by every prince in the land. At her tender age of fifteen, she has no immediate need of a husband, nor any plans of falling in love with any of the princes who have come to court her. The mischievous dwarf (aren't they all?) has plans of his own, and entraps the mother, getting her to promise Bellissima to him. He then traps the girl, making her promise to marry him before he releases her. This is a witty tale that would no doubt be quite frightening to young children (therefore they would undoubtedly like it). Happy endings were later additions to fairy tales by Disney. Don't look for a happy ending here, though it is certainly a good ending.

Arcalaus the Enchanter is thought of so highly by Lin Carter (as are the fantasy tales of Voltaire) that he had plans to publish entire volumes in the Adult Fantasy series for each of them. I am now a firm believer that Arcalaus, from a Portugese epic entitled "Amadis of Gaul," is one of the most imaginative adventures I have ever read. There is a fair amount of jousting, a visit to a very nasty dungeon, and an enchantment that holds our hero captive. Great imagination is unleashed here.

The Isle of Wonders is a second tale from "Amadis of Gaul," and is very much in the tradition of "The Sword in the Stone." Only one person can claim the prize. I plan on finding more of these delightful stories soon.

The Palace of Illusions, from "Orlando Furioso" by Ariosto and translated by Richard Hodgens, was another masterwork that Lin Carter wanted to bring into the series. He did manage to get one volume in, though he had plans for others, too. This is easily the finest tale of the thirteen in "Golden Cities, Far," and I can't wait to read the volume published later under the sign of the unicorn. Giants, a magic ring, a naked maiden chained to a rock, a hypogriff, a magic entrapment, a horn that when blown, terrifies anyone who hears it, and many other prime fantasy elements combine to make a great and highly entertaining tale!

In conclusion, Lin Carter has outdone himself with this fabulous collection of tales from historical and modern sources. One of the best in the whole series.

***** stars.

#23--Published November 1970

BEYOND THE GOLDEN STAIR

Hannes Bok

Cover art by Gervasio Gallardo

This is the second complete novel by Bok in the Ballantine

Adult Fantasy Series, following publication a year earlier of "The

Sorcerer's Ship". At the time, that novel did not make a great

impression on me, but images from it keep coming back to me. I will

likely reread it. The introduction to "Golden Stair" by Lin Carter is

fascinating, as we get a good behind-the-scenes peek at a (at the time)

living fantasy writer. This may be a good time to introduce some

thoughts on the series' cover art. Just about every aspect of this

cover is derived from an actual descriptive passage in the novel. This

has long been one of my favourite covers in the entire series. At this

point in my reviews, I have decided to go back and include both front

and back covers of panoramic scenes such as this. Watch for previously

reviewed two-sided covers to begin appearing. The covers of "Well at

the World's End", along with that beautiful title, are what first attracted me

to the series as a teen, and I am just as fascinated now as I was then.

The story divides into three parts. Part 1 deals with events

that lead our dysfunctional group of lead characters to the stairway.

Part 2 deals with the actual climbing of the stairs, while Part 3 takes

us to the magical and fantastic place that lies at the top of the

stairs. A short Coda at the very end brings us back down the stairs

again.

Part 1 is quite amazing and fun to read, as three criminals on

the lam escape into the Florida Everglades with a hostage in tow. The

three criminals, far from being portrayed in one dimension, are far more

interesting that the Utopian folk we meet later on. Frank, Carlotta

and Burke never disappoint us with their greed, violence, and petty

banter. Our captured hero, Hibbert, is a WW11 vet with a bum leg, and

is out of his league with this trio of low life, though he just barely

manages to hold his own in most situations.

Part 2 can be envisioned by looking at Gallardo's amazing cover

art. I think Bok would have been very pleased had he lived to see this

publication. The only real discrepancy between the written word and

the visual art is that Bok stressed that the stairs were moss-covered.

We meet the blue flamingo, and without giving away any of the plot, it

is not the same flamingo when we return to the blue pool at the end of

the novel.

Part 3 is a good example of the purest form of fantasy writing,

a bit like the writing in "A Voyage to Arcturus." I label this kind of

writing as the "I had a fantastic dream last night and I'm going to

tell you all about it!" type. If you think that listening to other

people's dreams is the highest form of bliss, then you will love every

sentence of Part 3. If, however, like me, you begin to yawn within

seconds of such events, then Part 3 may be a bit of hard going. Bok's

tale is somewhat saved by the three villainous characters of Scarlatti,

Carlotta and Burke, as they are made to reveal the reasons behind why

they turned out as they did. Frank Scarlatti manages to keep his past

to himself, no doubt much to our relief. To see how criminal buffoons

would react in Utopia is somewhat edgy writing. We keep wishing that

the intelligent, peaceful hosts would just put them out of their misery!

No such luck. Like many a Star Trek episode, the Utopian dwellers

(it's called "Khoire" here) do not interfere directly with the evil

characters, which turn out to be Carlotta and Scarlatti. They are left

alone to destroy themselves, and it happens in a way that is once again

reminiscent of a Star Trek episode. Burke manages to save himself

through great personal sacrifice, after committing a truly horrible

deed.

I enjoyed the novel, especially Parts 1 and 2. Part 3 is well

done and all, but to me it was anti-climactic. Half the fun was staring

at the cover and imagining what might be at the top of those stairs.

Bok's version is quite good, but so is mine! While

the cover art would be of interest to children, it is doubtful if the

story would. Show them the cover and make up your own bedtime story

about it. They will certainly love that.

*** stars.

#24--Published January 1971

THE BROKEN SWORD

Poul Anderson

Cover art by George Barr

This novel is an amazingly good read! The Ballantine Fantasy

Series itself is one of the most brilliant feats of fiction publishing

ever undertaken, and it is a book such as this one that makes the whole

undertaking worthwhile. This is the first fantasy fiction I have read

by Anderson, and it is an eye-opening experience. It is closest in

theme to the works of Tolkien and Walton (#18, above), though not very

close to either of them. Anderson knows his northern mythology as well

as either of those authors, however, and possesses one of the greatest

gifts of story-telling this reader has ever encountered. There are

gods, elves, dwarves, goblins, witches, trolls, giants, and even some

humans, but they are vastly different from such creatures encountered

anywhere, except perhaps in the original Norse myths. The Elven women

are especially interesting, being vastly different from Tolkien's

ladies.

Broken swords are common in myths, though this is the most

powerful one I have ever encountered. Getting it reforged is possibly

the most intriguing and entertaining part of the entire story, which

tells of two "brothers" and their hatred for one another, and how their

two stories intertwine and eventually, and fatefully, intersect. The

reforging part of the tale brought back memories of "Worm Ouroboros."

The many fierce battles, the cold blooded murders, treachery, revenge

and passion go far beyond that story, however, and even beyond Tolkien.

Such evil deeds happen to such good people that it almost seems real.

The story moves along at a rapid pace, and once going it is hard to put

the book down. Though spring and summer feature in the book, it is the

many wintry parts that I will long remember.

Snow, ice and bone-chilling cold feature prominently. One of the finest and purest fantasy tales I have ever read. Not suitable for children.

Snow, ice and bone-chilling cold feature prominently. One of the finest and purest fantasy tales I have ever read. Not suitable for children.

**** stars.

#25--Published February 1971

THE BOATS OF THE GLEN CARRIG

William Hope Hodgson

Cover art by Robert LoGrippo

I love well written sea adventure stories, and am a great fan of Joseph

Conrad novels, as well as Kenneth Bulmer's Fox series. Hodgson knows as much or more about the sea and sailing,

and has the power to put us in the boats with the stranded crew. This

is a spine-tingling adventure, containing one of my favourite opening

chapters. If, like me, you love Chapter One and what it promises, then

you will love the rest of the book. It is a short novel, easily read in

a weekend, and indeed it is hard to put down once begun. This was one

of the first Ballantine Adult Fantasy novels to enter my collection, way

back in my late teens. It was read and enjoyed not just by me, but

made the rounds of several appreciative friends, too. Like many of the

other stories in this series, it would undoubtedly make a great movie.

However, I find my own imagination quite adequate and up to the

challenge. Hodgson paints vivid pictures, especially night ones, and

the reader has no trouble envisioning the setting, characters and mostly

unseen horrors that plague the crew. This is a fun book to read, and

one can easily understand why Lovecraft had such great praise for it.

Jacket blurbs on books can't give much higher recommendation than

that! Not suitable for young children (as indicated by the author in the final sentence of the novel).

***1/2 stars.

#26--Published February 1971

THE DOOM THAT CAME TO SARNATH

H.P. Lovecraft

Cover art by Gervasio Gallardo

This

book of short stories by the master covers the years 1917 through 1924,

and does a fine job of showing Lovecraft's range. Nothing in here is

very earth-shattering, but there are many delights to sample. As usual,

Carter does a fine job of introducing these gems, and often allows

Lovecraft to speak for himself.

The Other Gods

is a very short story that opens the volume, telling the story of a

vain priest trying to achieve too much in his quest for the gods. His

discovery includes an unpredicted eclipse, in which he sees just a

little too much... A nice opening for this book, though nothing too

memorable for sophisticated readers.

The Tree

is a rather juvenile tale, though with an interesting setting.

Lovecraft rarely set any stories in ancient Greece. At this point, the

only thing that might keep a non-Lovecraft lover going is that the very

next tale is the title story. Let's give it one more try.

The Doom That Came to Sarnath

is a memorable tale, and Gervasio Gallardo's cover painting gives a

sneak peak into a great city's ultimate demise. It takes rather a long

time for events to finally catch up to Sarnath. Something fun in

Lovecraft is that in other stories he will occasionally mention events

and places from some of his other tales, and Sarnath appears elsewhere

more than once.

The Tomb

is a very Poe-like tale, almost lifted from that master's oevre. These

days we would label this as "fan fic." Still a fun read, but would

likely be ignored if it weren't by Lovecraft.

Polaris is a story about a man's guilt complex at involuntarily aiding the destruction of his once fabulous city. Not very memorable.

Beyond the Wall of Sleep

is a slightly longer tale, telling of the strange person named "Joe

Slater." Studied closely by our hero, an asylum worker where Joe is

kept, there are some key theories espoused by Lovecraft in this readable

piece, especially concerning dreams.

Memory

is a one-page piece in which a genie of the moon comes down to speak to

the demon of the valley, inquiring about the stone ruins that are

scattered about. The story is a trifle, but is a good reminder of how

insigficant it all can seem, depending on one's perspective.

What the Moon Brings

is a mere two pages in length. How could anyone hate the moon?

Perhaps someone who is a lunatic, and sees things that the rest of us

do not.

Nyarlathotep stretches to three pages, and has at least one prophetic passage!

"There

was a demoniac alteration in the sequence of the seasons--the autumn

heat lingered fearsomely, and everyone felt that the world and perhaps

the universe had passed from the control of known gods or

forces to that of gods or forces which were unknown."

The tale speaks of a person who comes out of Eygpt with

knowledge of things old and full of mystery, after sleeping for over 27

centuries. The Egyptian (who looks Pharoanic) invites the citizens to a

showing of shadows and electrical wonders. It takes some time, but

once realization of what was seen sets in, the end isn't far behind. I

like this little story because of those shadows--the horrors are hinted

at, but the repercussions are made obvious.

Ex Oblivione

is another two-page quickie, this time concerning another who is tired

and living and seeks his way through the secret gate. With the use of

drugs and dreams he is finally able to enter the gate, though he gets a

bit more (or rather less) than he first expected. Nicely done, though

nothing too original.

The Cats of Ulthar

also appears in "The Young Magicians" (#6, above), and like, Doom That

Came to Sarnath, is a tale of vengeance, albeit belated. Score a big

point for the cats!

Hypnos

is another one of those great little tales where the sighted horrors

are not described to the reader, but merely hinted at. Finding a fallen

stranger and looking after him ("...a stranger who seemed to be "a

faun's statue out of antique Hellas, dug from a temple's ruins and

brought somehow to life in our stifling age..."). Studying unworldly

subjects together, traveling in dream to places never before seen.

This is a poetic tale of woe, and at seven pages it reads like a two

pager, with a fun "surprise" ending.

Nathicana

is a short poem, and to be perfectly honest I would rather have a

mediocre one page story. Poe could write prose and poetry, but

Lovecraft's poetry, at least in this instance, should be left alone.

Either give more examples or none at all.

From Beyond

introduces the reader to a machine that will allow us to "...overleap

time, space and dimensions, and without bodily motion peer to the bottom

of creation." Of course that is the easy part: staying sane afterwards

is infinitely more difficult. This a fun tale of a former friend who

breaks off relations from everyone, but calls his best friend back to

show him his machine and what it can reveal. Some things are best left

unseen.

The Festival tells

of a Yuletide visit by one man to his ancestral town, and of the quiet

welcome he receives. The town he visits is not the one intended,

however. This would have made a terrific Twilight Zone episode,

especially with its surprise ending. We get a good look at the Necronomicon, and not just the one borrowed from the library at Miskatonic University at the end of the tale.

The Nameless City

is one of the best stories in the book, and a superb example of

Lovecraft's imagination unleashed and carefully under the control of his

unique writing craft. It reminds me of Clark

Ashton Smith, but with a much more distinct flavour of Lovecraft himself. The ending is

nicely linked to a small detail near the beginning. Definitely read

this one.

The Quest of Iranon

also appears in Vol #6, above. I'm not sure if Iranon is Lovecraft's

way of saying "irony," but this sad tale of a dreamer--whose dream is

exposed for what it is--is quite stunning, and ironic. The stories are

becoming better and better now.

The Crawling Chaos

is the first of three concluding stories that were collaborations with

others. This tale concerns the travels of an opium user, and has the

feel of authenticity to it. The destruction of all things is witnessed

and described, and includes some of Lovecraft's most colourful and vivid

descriptions.

In the Walls of Eryx

is a science fiction story, something quite rare in Lovecraft's oevre.

Again we have the makings of a decent Twilight Zone episode, as we

accompany a mineral gatherer on Venus as he wends his way to his unique

destruction. Though flawed, the story is no worse than much pulp sci fi

that was being published at the time, and though the idea is sound, not

enough care was taken to make it completely believable. Would this

person really have been out all on his own in such a hostile

environment? Why was he not carrying any type of communication or

signalling device? Also, the motives of the aliens were not made clear

enough. With just a bit more thought this could have been much more

satisfying, though I still enjoyed it. This is the longest story in the

volume, but it reads easily and quickly.

Imprisoned With the Pharaohs

comes from an idea by Harry Houdini, but turned into a minor

masterpiece by Lovecraft. There are no loose ends or obvious flaws with

this tale of an escape artist being tricked and kidnapped, then lowered

(and lowered) deep into a tomb in Egypt. This is classic Lovecraft,

with definite elements of Poe lingering in the atmosphere.

While the volume is a must for Lovecraft fans, many of the

stories are just not memorable enough to convince non-fans of his great

talent. However, by selecting a few of the stories (Nameless City,

Imprisoned with the Pharaohs, The Crawling Chaos, The Festival) it

should be easy to prove Lovecraft as one of the greatest fantasy writers

who ever lived.

*** stars

#27--Published March 1971

SOMETHING ABOUT EVE

James Branch Cabell

Cover Art by Bob Pepper

Ballantine Books printed several of the very best works by

Cabell, and this novel is right at the top of them all. Since I began

"to get" Cabell's writing (something I was unable to do on a few

previous attempts, including with this book), they are among the most

looked-forward to volumes in the series, as I read them all for the

first time, in published order. I'm not so sure I would begin with this

volume if I were a Cabell neophyte. I would recommend Figures of Earth

first, then any of the others. I am not certain how easy these books

would be to read if English is your second language, and am even less

certain how things would go if Cabell were translated.

Something About Eve concerns the travels of a 20th C.

descendant of Dom Manuel. His epic fantasy voyage leads him to

adventures of the Cabell sort, with dialogue to die for and characters

and situations one could never encounter with another writer. The

peculiarities of situation and character are what drives Cabell's

stories, and this is perhaps the finest of them all. We encounter many

famous persons from history along the road, and the conversations are

sublime and divine, to say the least. The goal of our hero lies, of

course, at the end of the road, though whether he makes it there becomes

less and less significant as the story moves along.

This is very, very sophisticated writing, but do not be put

off. Every word is important, and every page worth reading twice, but

even a quick reading at first is better than no reading at all. If this

is your first Cabell, then I wish you luck. Being my fourth or fifth, I

am now an avid fan, and will seek out other works by the author beyond

this Ballantine series. The book is of no interest whatsoever to

children.

**** stars.

#28--Published March 1971

RED MOON AND BLACK MOUNTAIN

Joy Chant

Reprint Cover Art by Ian Millar

Original Cover Art by Bob Pepper

Not only is this a seriously flawed novel, but it is not, by any definition, adult fantasy. Despite

Lin Carter's assurances to the contrary, this novel is aimed directly

at early teens. One must understand those heady days after Tolkien had

completed Lord of the Rings. Everyone and their animal companions were

writing another Tolkien masterpiece (including yours truly). Most of us

did not see our great masterpieces of fantasy fiction reach

publication, but somehow a few others squeaked through. Publishers were

desperate to discover the next Tolkien, and Chant's first novel is

certainly not it. I could spend a long time discussing the weak points

of this novel, but I will only name a few. This is a bad pastiche of

parts of Tolkien, C.S. Lewis and others who were writing heroic fantasy

at the time. It is clumsy storytelling, and should never have been

included in this series. It is not Joy Chant's fault that she does not

measure up to Tolkien, Dunsany, Morris, Lovecraft, Smith and others in

this series, and I do not hold this novel against her. However, what

were Carter, Ballantine and Unwin and Allen thinking??!!

We soon have a battle between white eagles and black eagles

taking place (good grief!). We are never told why this battle is taking

place, nor why the people watching do not assist the whites. A few

well-placed archers could have been a big help here. Then the eagles

are promptly forgotten and never reappear again. The battle, which is

well crafted by Ms Chant, has no significance whatsoever to the rest of

the tale. The tale soon becomes so formulaic as to be actually tedious

at times (woman and girl imprisoned in high castle tower, rescued by man

who can shoot arrows and climb like a monkey, and get through all

manner of security), and I find it somewhat hard to believe it won the

Mythopoeic Award for 1971. One must wonder about the competition that

year. The three children that were transported here somehow are in

every scene, either singly, in pairs, or as a threesome. One soon

begins to wonder where Aslan the Great Lion is at. We do have a miraculous

horse (with a unicorn horn) that seems to know everything about

anything, and Galadriel and Celeborn seem to be there, too. Strider

appears as "The Borderer," surely one of the most awkward character

names in fantasy fiction (though, like Strider, he is a pretty cool

fella, who appears then promptly disappears again).

I will skip over any number of minor flaws and jump to the main

battle near the end of the book. It appears that the captain of the

dark things wants to come outside, and not to play nice with his

friends. No; quite surprisingly he wants to rule the world, and will

cheat and do almost anything to gain this title. It would really be to

his advantage if the battle could be fought when his moon (the red one)

is full and their moon (the silver one) is just beginning to wane. So,

of course, the good guys have no choice but to give him his wish.

Wouldn't want to upset him, after all. He might become even nastier.

The good guys send in their 16 year old hero, Oliver, from somewhere

else. He is really, really scared, despite having been trained to fight

and already coming from a previous battlefield quite successfully. In

case we didn't get the message, we are told again and again how scared

he is of fighting against the main bad dude. The bad dude uses evil

magic to confuse Oliver, and even when our hero strikes the winning

blow, it doesn't count since the dark magician cannot be hurt by weapons

or people from this world. Oliver's sword melts or something after he

stabs the bad guy. Good thing Oliver is from a different world, and has

a knife with him from somewhere else, too. Despite being at a huge

disadvantage (one could even say the dark guy was cheating

considerably), Oliver kills the dark leader in single combat in front of

both armies.

Boy, does he ever regret it later. He feels terrible at having

killed someone. Really terrible. Really really bad. And we are told

again and again. He really shouldn't have killed that nasty, cheating,

creepy dark magician who wanted to rule the world. Perhaps Oliver

thought a little chat would have solved everything. Despite their

leader literally going up in smoke, the dark army still attacks, though

they lose the battle. Oliver feels worse and worse about things, until

he can barely function. Finally, at the very end, he offers himself as a

sacrifice to bind the earth magic (or some such thing). Lucky for him

he doesn't really die, but he and his brother and sister are taken back

to their own time and world. The end.

To be fair to Chant, there are times when she writes well,

especially near the end. But the lack of finesse and basic storytelling

skills are so lacking much of the time (we never actually learn

anything about the bad guy, other than he is bad and wants to rule the

world), and his army lives and dies as just an unknown amorphous blob.

The map that comes with the book is less than helpful (likely partly

Ballantine's fault), and is filled with places we never find anything

about or visit. Most of the action takes place in one little corner of

this giant continent. Then there is the dizzying array of names we must

learn, most of them beginning with the letter "K". A glossary would

have been most helpful, though even so there are just too many names for

this length of book. Many of the names are not that important to the

story anyway.

In conclusion, the novel reeks of "first published book," and

not in a good way. I would much rather re-read any of the Narnia books

than this novel. However, seven years later Chant published a prequel

to "Red Moon and Black Mountain." "The Grey Mane of Morning," at least

in my copy, has a much better map, and it has a glossary!! It also has

an introduction by Betty Ballantine, and is illustrated throughout by

Martin White. Published by Bantam Books, it is rather a handsome

paperback edition. In fairness to outraged fans of Joy Chant who might

be reading this review and plotting my death by dark magic, I am going

to attempt this second novel. However, in fairness to me, I am going to

give my honest opinion of it right here, as soon as I am done reading

it...

*1/2 stars. Suitable for young teens.

The Grey Mane of Morning

Joy Chant has created a minor masterpiece with her brilliant,

well-thought out and very carefully paced 2nd novel. No doubt had the

Ballantine series continued indefinitely, this book would have been

included. It is so vastly different and so much more mature than the

first novel, it seems as if someone else had written it. Ms. Chant

certainly polished her writing skills before allowing this to be

published. The story has nothing whatsoever to do with Red Moon and Black Mountain,

other than being in the same world but in a very different time. I

highly recommend this novel to adult fantasy lovers, even if you (like

me) did not like her previous novel very much. This one is completely

original in concept, and handled well on almost every page. There is

only one chapter I did not find up to the same standards as the rest of

the book. Chapter 21 has Mor'anh (the hero) literally meet and talk

with his God. Rather shabbily done. That, for me, was the only low

point.

***1/2 stars. Not recommended for children, though older teens might like it.

When Voiha Wakes

This short novel (160 pages) is once again a flawed product,

making me wonder who really wrote that 2nd book! I find it amusing that

this book and the first one won Ms Chant the Mythopoeic awards for their

respective years, but her best work (Grey Mane) was runner up. This is

a "women's" fantasy book, which is certainly not bad in itself.

However, we are expected to accept a very civilized society where women

rule, men sleep in a different city than the women, there is no love

between them, there is no violence anywhere, and there is no such thing

as real music or musicians, at least in most parts of this world. All a

bit of a hard pill to swallow. There are plenty of beautiful boys,

though, and any amount of pottery and woodwork. Give this one a miss.

*1/2 stars.

#29--Published April 1971

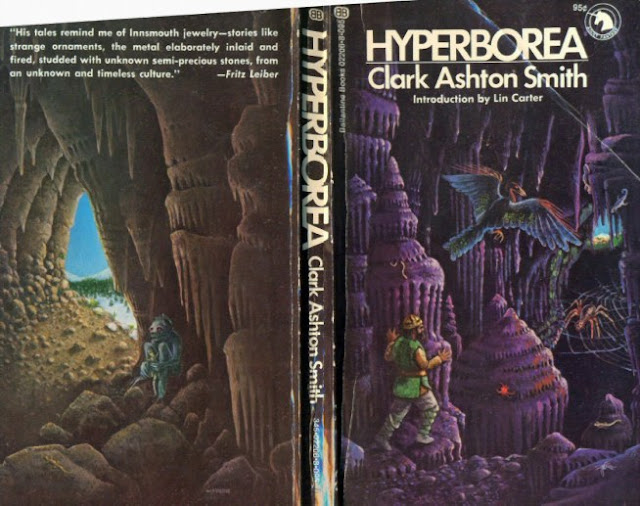

Hyperborea

Clark Ashton Smith

Cover art by Bill Martin

Smith has become one of my favourite fantasy authors since I

began embarking on my collecting and reading/rereading project of the

Ballantine series. I had never read any Smith before last year. I

think it is very appropriate that Fritz Leiber gets the back cover blurb

(the cover is not damaged; I scanned it at a bad angle and had to lose

some perspective when I straightened the image on Photoshop). These

stories remind me very much of the Lankhmar adventures, and though Smith

never uses the same hero throughout as does Leiber, the adventures have

a familiar ring to them. Since Leiber is one of my very favourite

authors of all time, particularly his sword and sorcery tales, I dove

into this book like it was a box of chocolates. As in the previous

Smith volume (Zothique, #16, above),

Carter has collected all the tales by Smith from a certain continent,

and has even taken it upon himself to include a map again. Not all the

stories are of equal quality, but the good ones are very, very good.

(This is the eve of a long vacation for me, so I will not be

writing about each tale at this time--when I return in early Sept. I

will try and make sense of my notes and talk about all of them then).

For now, I would just like to mention my favourite ones. There seems

to be more humour in this volume, though the horrors can be just as

terrifying. "The Coming of the White Worm" is a great tale of woe.

"The Door to Saturn" is really strange, like a bad LSD trip. "The Ice

Demon" features two thieves whose adventures are strongly reminiscent of

those of Fafhrd and Mouser, while "The Tale of Satampra Zeiros" and

"The Theft of the Thirty-Nine Girdles" continue in this vein, with a

strong flavour of Arabian Nights. The latter two tales feature the same

hero, the first a story from his youth, and the second from later

years, and both are classic Smith at his very best. The cover painting

illustrates a scene from the first main story, "The Seven Geases," one

of many that features strong irony, especially in the way it ends.

Hyperborea itself is supposed to resemble Greenland millions of

years ago when it was steamy and warm. We see it then and also as the

ice advances. If Hyperborea does not have the same level of paranoia as Zothique,

it has just as many elements of surprise, wonder, horror and creative

style to make the book worth several readings. As the Hyperborea

stories are rather short and few in number, Carter has included a few

other snippets by Smith to fill out the number of pages. In my view, it

wasn't necessary to do this, but I am glad he did. Not recommended for

young readers.

***1/2 stars.

#30--Published May 1971

Don Rodriguez: Chronicles of Shadow Valley

Lord Dunsany

Cover art by Bob Pepper

Not to take anything away from this wonderful story, Lin Carter

was stretching things just a little by including this volume in the

adult fantasy series. Firstly, the location is firmly set in Spain and

the Pyrenees. Though the date is a little ambiguous, we know it is near

the time when gunpowder was first being used in battle. Very little

magic is involved. In fact, only one of the twelve short chronicles

could be classified as purest fantasy. Everything else that happens in

the book could have actually happened as described, though the last

chronicle, describing the building of Don Rodriguez's castle, does

stretch reality to the limit.

Since it is a moot point to discuss whether the book should or

should not have been included in the series, I will limit my discussion

to a critique of the novel itself. It is Dunsany's first full-length

novel (he wrote ten), and I must say it is a very good one. Each

chronicle describes a minor or major adventure our hero must survive.

The first is a chilling horror tale, worthy of Poe or Lovecraft, and

this short tale really put me in the mood to read the rest of them.

None of the others reach the same level of decadence, but the fourth

tale details how Don Rodriguez and his companion (think Frodo and Sam--there is

also an awful lot of traveling in these pages; on foot, horseback and

small watercraft) travel to the Mountains of the Sun. If, like me, you

are an enlightened person with a good working knowledge of science, and

you think that the sun does not have mountains, then think again. They

do, and Don Rodriguez has seen them. This tale is a highlight for me,

one of the finest short fantasy pieces I have ever come across. And

it's made me think of solar flares and sunspots with a whole new imagery

arsenal!

Though Don Rodriguez is a very serious man, there is humour

aplenty within these pages. Morano's frying pan has a lot to do with

it, and soon becomes a third companion on the voyages. The duel between

Don Rogriduez and a better swordsman will never be forgotten once it is

read. Don Rodriquez's mandolin is also an important component of the

novel, becoming more-so as the story progresses. Don Rodriquez has a

goal throughout, and he sticks to it religiously, letting nothing

interfere. He wants to go to war and win a castle for himself. After a

long search he does find his war, but the castle that he wins is not

all he expected. The war will not be what the reader expects, either.

Dunsany's prose here is probably one of the finest examples of

understated word power I have ever come across. Though there are flaws,

especially in the final chronicle, the writing is probably among the

best things Ballantine ever published. "Daydream-like" does not capture

what Dunsany achieves, but it is a start. As usual for this series, I

really took my time reading, especially as a long journey is involved in

the story. I wanted to feel as if I was on that journey, and if I read

the book in one night or afternoon, then it is hard to feel that way. By reading

one Chronicle each day, however, the book becomes the epic it was

intended. I highly recommend the book--just don't expect a lot of

fantasy. Children would not likely be impressed.

**** stars

Mapman Mike

No comments:

Post a Comment